Neville Hall is a finalist for the 2021 SOUNZ Contemporary Award | Te Tohu Auaha for his orchestral work 'so flamed in the air'. We caught up with Neville to find out more about the piece, and about life in Slovenia during the pandemic, where he has lived since 1993.

Can you tell us a bit about ‘so flamed in the air’?

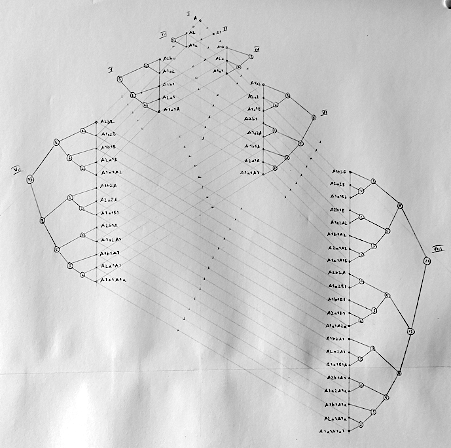

Almost all of my music is based on networks of musical events, with the events being conceived more or less as timbral entities, that is, their identity is independent of pitch and is determined instead by sculpted combinations of instrumental sound. The individual events are created by simultaneously developing and deconstructing a central musical idea, but the specific configuration of each network depends of the formal processes at work in the particular composition. These processes always involve some form of organic growth, so that longer and longer formal units gradually take shape, all constructed from closely related material.

There are many ways the resulting formal units can be deployed in the final composition: they can be layered in single movements, presented separately, juxtaposed or interspersed with individual events from the network, etc. In ‘so flamed in the air’, the formal units are deployed as seven separate movements, each of which represents a rounded phase of growth exploiting material from a new, expanded ‘branch’ of the event network. The original event is heard in its entirety in the second movement, and then again in a fleshed-out version in the last movement, entitled ‘Epilog?’. In terms of phases of growth, the sequence of movements is: 3, 1, 4, 2, 5, 6, 1. One consequence of this way of working is that the development of ideas is scattered over time, and there is a constant play of semblance between the different movements as related material takes on ever new guises in new contexts.

Of course, this is a description of the idea embodied in the technique of the work, and it doesn’t capture its musical sense, but I don’t believe in the notion of instrumental music having a ‘topic’, or in linguistic descriptions of musical sense, so in this respect I’ll follow Wittgenstein’s maxim from his ‘Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus’: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”.

'so flamed in the air', network of musical events.

How did this commission come about?

In 2019, the management of the Slovenian Philharmonic was taken over by Matej Šarc, who had formerly served is the principal oboist in the orchestra for decades. Matej is also the leader of the Slowind wind quintet, who, in addition to their own concerts, have organised a superb festival of contemporary music in Ljubljana for more than two decades, inviting top composers and contemporary music ensembles as guests. I served as the artistic director of the festival in 2005. Matej is the driving force of contemporary music performance in Slovenia and is very knowledgeable about contemporary music. As part his reorganisation of the activities of the Slovenian Philharmonic, he introduced a series of concerts dedicated entirely to contemporary music in the 2020/2021 season (and removed contemporary music from the programmes of the regular subscription concerts). One of the concerts focused on the leading Italian composer Salvatore Sciarrino, who had agreed to attend the event in person and present some workshops in Ljubljana. The other composer on the programme was Luigi Nono, who was a logical choice considering his association with Sciarrino. The concert was conducted by Italian conductor Marco Angius, who is a Sciarrino specialist and has recently published a book about Sciarrino’s music.

Matej wanted to include a new work by a local composer on the programme and felt that my music would be appropriate in this context, so he commissioned a piece from me. I had recently finished a piece for the RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra (entitled ‘Or Looked back to the flowing’), which was scored for a very large orchestra, and I’d been thinking of writing a more intimate piece for a smaller orchestra, so I was very happy to receive the commission. ‘so flamed in the air’ is scored for an orchestral ensemble with double wind, strings 66642, two percussionists, harp and piano.

Unfortunately, the Covid virus spoiled the party, and none of the concerts from the contemporary music series were performed live. In fact, the Slovenian Philharmonic only managed to present a couple of concerts at the beginning of their previous season before the whole thing was closed down. Thankfully, some of the concerts were performed behind closed doors and live streamed, including the concert with my new piece. Sciarrino wasn’t able to attend and the programme had to be changed slightly to include pieces that could be performed on a smaller stage with social distancing between the players, but Marco Angius made it to Ljubljana and did a great job of preparing the orchestra.

Did the other pieces on the programme influence your work?

Of course, I don’t change the way I compose depending on which other pieces I share a concert programme with.

When I first came to Europe in the early 1990s, there were six composers who had a big influence on my work. Two of them I had never heard of before leaving New Zealand (Salvatore Sciarrino and Helmut Lachenmann); two of them were already known to me, but only through a couple of pieces (Giacinto Scelsi and Gérard Grisey); and two of them were familiar to me, but I hadn't really understood their work (Brian Ferneyhough and Luigi Nono). I attended Brian Ferneyhough’s summer course in Szombathely, Hungary, in 1997, and I had the good fortune to have a private lesson with Gérard Grisey in his apartment in Paris just a couple of weeks before he died suddenly in 1998. Apart from that, I was going to a lot of concerts in nearby centres like Vienna and Venice, as well as collecting piles of CDs that hadn’t been available in Auckland while I was studying there (that was the pre-Internet world, so access to new music was limited).

Although I already had quite a lot of momentum in terms of compositional technique when I arrived in Europe and I knew more or less where I wanted my music to go, it took me about a decade to digest these new influences and reconstruct my own authentic musical voice. When I look back at my compositions from 20 years ago some of them seem a bit over complicated, which probably reflects the fact that I hadn’t yet fully processed the influence of Brian Ferneyhough especially, but I’ve been following my own path for a long time now and I’m not really influenced by what other composers do. These days I feel closest to the music of composers of my own generation, especially Rebecca Saunders, Mark Andre, Stefano Gervasoni, Alberto Posadas, Beat Furrer and Elena Mendoza, among others.

Performance of 'so flamed in the air', (starts at 10:05).

You often draw on Ezra Pound’s Cantos for your titles. How did this start, and what keeps you coming back to the Cantos?

Titles introduce a splinter of language into instrumental compositions that can, I think, often be misleading, giving the impression that the composition is actually ‘about’ something, that it has a topic. Different composers have different creative processes. Some composers need the support of a topic when they compose and they can come up with fantastic pieces working in this way. Whether the pieces actually embody the topic is another question. If that were the case, the audience would be able to identify the topic of an instrumental composition without the hint provided by the title; for example, if a composer wrote an instrumental piece about the topic ‘imprisonment’ (as Slovenian composer Vinko Globokar has done), the listener would be able to recognise that the piece was about imprisonment without knowing the title of the piece. This is clearly not the case. You could argue that the title somehow enables the listener to understand what the composer is ‘trying to say’ in his/her piece. The problem is that if you label a piece ‘Imprisonment’, some of the audience will manage to find associations with imprisonment, but if you label the same piece ‘Freedom’ those same people will find associations with that concept instead. In the end, it just becomes like seeing images in clouds and, in my opinion, it distracts from the genuine musical sense of works.

So what is the solution to the title problem? When I was a student, I tried to give my pieces titles that reflected something about the way they were composed; for example, ‘Configuration’, ‘Reflexive’, ‘Branching’, ‘From a Single Point’. At a certain point, these titles struck me as being too cold and they didn’t reflect my attitude to music, which is essentially poetic. So I started to come up with more poetic titles, often incorporating the words ‘silence’ and ‘time’; for example, ‘a splinter of silence in the belly of time’, ‘silence rain down, quenching time’s fire’. Finally, I realised that if I wanted to use poetic titles for my pieces it would be better to turn to a real poet. That’s when Ezra Pound entered the picture.

My affinity with Ezra Pound has a strange beginning. When I was at secondary school, the brother of a friend of mine had a band called ‘Ezra Pound’. If it hadn’t been for that I probably wouldn’t have been aware that Ezra Pound was the name of a famous poet (his name never came up in English classes at school). Later, I started to notice his name in association with works by Italian composers, such as Berio’s ‘Laborintus II’ and Nono’s ‘Guai ai gelidi mostri’, so when I thought about borrowing titles from a real poet, the first person to come to mind was Ezra Pound. In the late 1990s, I bought a copy of ‘The Cantos’ (which is 800 pages long) as well as a book with an analysis of the poems (which is 700 pages long) and spent a lot of time absorbing and trying to understand the work. Since then, ‘The Cantos’ has been a lifelong companion.

Every time I start a new work, the first thing I do is dip into ‘The Cantos’ and make a short list of possible titles. Once I remove a fragment of text from its context it takes on a life of its own and inevitably ends up having musical implications in my own mind, implications that hover over my desk as I compose. For example, the context of ‘so flamed in the air’ is:

And as the olibanum bursts into flame,

The bodies so flamed in the air, took flame,

When I took ‘so flamed in the air’ out of this context, I started to imagine it as referring to sound, the way ripples of sound pass through the air like flames. Of course, this is entirely my own idle fantasy and has no conscious bearing on my approach to the music.

On the topic of having a lifelong connection to a particular poem, I’ve just been reading Kenzaburō Ōe’s beautiful quasi-autobiographical novel ‘Death By Water’, in which the central character and narrator has a lifelong affinity with T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ (a poem that is coincidently dedicated to Ezra Pound and paraphrases a line from ‘The Cantos’ that I used for a piece for violin a cello: ‘From time’s wreckage shored, these fragments shored against ruin’). I just mention this because I could relate to the idea of living with a particular poem over a long period of time (which I totally recommend to anyone who hasn’t done this already!).

'so flamed in the air', fifth movement, first violins, bar 10-12.

Living in south-central Europe, how has your experience of the pandemic been?

Slovenia was in total lockdown from about March to May in 2020, and then in various forms of lockdown from about October 2020 to June 2021. During the first lockdown, the streets were empty and most people were really careful about social contact, resulting in near elimination of the virus in June 2020. In the second wave of lockdowns, there were so many exceptions – combined with a high level of apathy (or Covid fatigue) and a low level of cooperation – that the virus continued to be present to some extent throughout the summer (which has just finished). Now we’re approaching the peak of the so-called fourth wave and there are currently over 1000 new infections each day (in a population of two million). Fortunately, the level of hospitalisations and deaths is lower than before due to vaccination, but only about half of the population in Slovenia is vaccinated and the government (which has a shaky legitimacy and enjoys a very low level of trust) is having real problems convincing the other half. Although there are no new lockdowns planned, more and more aspects of public life are being restricted to people who are recovered, vaccinated or tested.

The way the virus has been managed in New Zealand is amazing. It reflects the solidarity and humanity of NZ society.

Has the situation changed over time?

It has been the story of a gradual journey from fear to acceptance and a new normality. Like a lot of people, I had Covid earlier this year. Fortunately, in my case it wasn’t too bad and my family weren’t infected. Having experienced it reduces the fear factor. Those of us who are recovered and/or vaccinated can live more or less normally at the moment. As in other places around the world, there’s a lot of debate about mandatory vaccination. It’s an ethical minefield. In general, there’s a lack of social cohesion in Slovenia, which makes combating the virus very difficult.

How are the arts affected in Slovenia at the moment?

Performing arts were virtually eliminated in the 2020/2021 season. Thanks to vaccinations, things are looking much better for the season that is just getting under way, but you never know what’s around the corner. If intensive care units start to fill up again, there might be tighter restrictions even for those of us who are vaccinated and/or recovered.

Neville Hall's 'Or looked back to the flowing' from his new CD of the same name.

What projects do you have lined up for the future?

My orchestral composition ‘Or looked back to the flowing’ (which is also the title track of a CD I released last year) has been selected to represent Slovenia at the International Rostrum of Composers in Belgrade next month, so – virus permitting – I’m hoping to go down to Belgrade with the RTV Slovenia delegation. Next week, we’re starting rehearsals for a new piece I’ve written for clarinet, cello and accordion, entitled ‘more full of flames and voices’. At the moment, I’m writing a piece for four female voices (two soprano/alto pairs). Apart from a couple of early choral pieces, I haven’t written a lot of vocal music because it took me a long time to work out how to deal with the interface of text and music in a satisfactory way, but over the last few years I’ve been listening a lot to the madrigals of Monteverdi and Gesualdo, and this has somehow helped me to find a solution that I’m satisfied with (for now). My new piece is entitled ‘not a ray, not a slivver’, and you can probably guess from where I’ve taken the fragment of poetry that it sets.