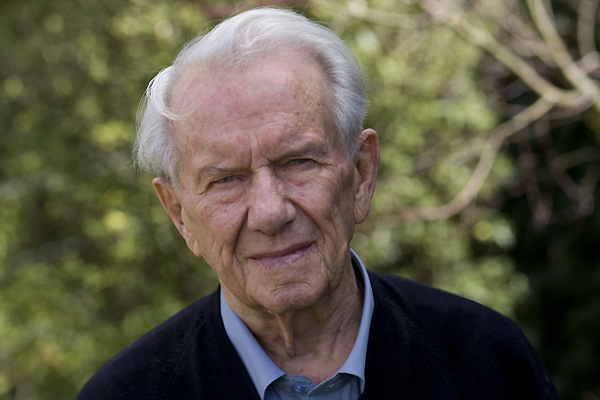

On September 29 this year my father, John Ritchie, would have turned 100. Being a cricket fan, he would have appreciated the century milestone but, as it is, he had to be content with a very creditable 93 (he died on his birthday, in 2014). He was pleased as Punch when his 90th birthday was celebrated in style by Christchurch musicians, and by a superb book compiled and edited by Philip Norman.

When Dad was born, Strauss, Rachmaninov, Ravel, Elgar and others still roamed the earth. He was not to hear their music until later in life, owing to a precarious start to life. John was born out of wedlock to a young woman, Jessie Harrison, and a much older man, John Thain Ritchie. The parents separated when John was 8, and he was brought up by his father and attended boarding school in Wellington. His father then died when John was 12, and consequently he was sent to Dunedin to be cared for by relatives. It was his good fortune to be sent to King Edward Technical College where a musician, Vernon Griffiths, was undertaking an experiment whereby all pupils at the school (no exceptions!) had to sing and learn an instrument. John learnt several instruments, including clarinet, tuba and cornet, and started composing under Vernon’s guidance. He also met my mother, Anita, who was a promising soprano, at school (at a music camp in Pūrākaunui, to be precise). Naturally, he wrote songs for her.

This happy outcome after a rough start to life was clouded by the arrival of war; my father completed a music degree at Otago University in two years in order to enlist in first the army, then the navy and finally the air force (flying Spitfires). He was one of the lucky ones who spent considerable time abroad but saw little action. Following the war, John was appointed as lecturer in the School of Music at Canterbury University, where Vernon Griffiths was head, and thus started a career as an academic, composer and conductor that spanned from the 1940s through to the 1980s. He was still composing into his nineties. John composed over 300 works over his career, and also conducted the NZ Symphony Orchestra (or National Orchestra as it was known then) as well as helping to establish the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra. He helped establish performance as a major discipline at the university, and became professor and head of School of Music in the 1960s, and eventually acting Vice-Chancellor. One of his composing highlights was being asked to write music for the ceremonies at the 1974 Commonwealth Games. Further details of my father’s life have been well surveyed in a recent PhD from Waikato University, by Julie Johnson, as well as the Norman book mentioned above.

My father was influenced in his early days by the English school of composition, via Elgar and composers such as Finzi, Howells and Walton. This was encouraged, of course, by Vernon Griffiths, himself an anglophile. In 1957, however, John upset Vernon by opting to take his sabbatical leave in the USA instead of the expected destination, England, or “home”. John sensed that he needed ‘freeing up’ as a composer, to escape the somewhat stuffy atmosphere of contemporary English music. So, he studied with Walter Piston in the states, and discovered Stravinsky, Bartok, Barber, Copland and other composers of a very different ilk. John’s best known composition, the Concertino for Clarinet and Strings, was written in this same year and shows some of these new influences at work; dissonances are sharper and resolve less frequently, rhythms are punchy and unpredictable, tonality is freed from major/minor dominance. The work was recorded onto LP by the Alex Lindsay Strings in the early 1960s, along with Farquahar’s Ring Around the Moon suite and Lilburn’s Landfall in Unknown Seas. It became one of the sound-tracks of my youth; my brother and I included the Concertino in our Top 20 list, under the label “Dad’s music”.

Following his experience in the USA, John continued to look outwards, globally, rather than following the Lilburn-esque search for national identity within Aotearoa. In 1967, on another sabbatical, he spent time in Europe and the USA, and made connections with the Prague String Quartet, who eventually enjoyed a residency at Canterbury University. Later, he became president of ISME (International Society for Music Education), meeting with composers such as Kabalevsky (USSR) and Ginastera (Argentina) and also making connections with the Kodaly Institute in Hungary.

Many people in Aotearoa assume John Ritchie was essentially a community composer, and indeed, he did write a lot of music to demand for community occasions. However, this is just one side of his work: as indicated above, he looked outward in an international sense. A good example of this ‘other side’ of his work is his song cycle Four Zhivago Songs, published in the 1977. Using texts by the dissident writer, Boris Pasternak (who’s famous novel Doctor Zhivago was banned in the USSR), these songs explore a modernist world of angular melody, spicy dissonance and interesting timbre. I used to wonder why my father had not written more works like this but now understand that this was due to circumstances more than anything else; he had few opportunities to compose commissioned free of an occasion. For most of his career there was no Arts Council providing funding for projects. My father was also up against the perception that the Christchurch musical scene was conservative; I know he felt aggrieved that he had few opportunities to compose for leading musical organisations, such as the NZSO. In later years I had the impression that my father regretted not writing more ambitious works, such as a symphony or an opera. However, his life was incredibly busy as it was, with the full-time academic load, the myriad of conducting gigs, plus a family of five children.

My father was an interesting mix of open-mindedness and conservatism. In his university role, he encouraged several young composers into academic positions, including John Cousins, possibly the most radical composer of his time that Aotearoa has produced. He had an attitude of ‘live and let live’ even if he didn’t always enjoy what the more experimental composers were producing. I remember him telling me to try and retain my sanity in a mad world. He was always very positive about my work even when, I’m certain, he didn’t always enjoy it.

He was also a curious mix of religiosity and secularism. The Zhivago songs I mentioned above are a good summary of this. John identified with the ‘saint and sinner’ that is within the character of Zhivago, a man doing good deeds in the world but also maintaining an extra-marital affair. I’ve often wondered if his Catholicism encouraged this with its obligatory confessional, allowing a person to be absolved of sins on a regular basis. As a father, he was often absent due to his very busy workload and pursuit of career, but the times we did have together as family were generally happy, in my memories. My four older siblings have different experiences to relate, but we managed to maintain meaningful relationships with him throughout his life.

People often ask me what was it like having the role model of father as composer? I can honestly say it didn’t seem strange. I got used to seeing my father’s manuscript and ink from an early age, and from the sounds of classical music in the house, so it never seemed odd to try my hand at composing, and consider a career as a composer. Once I reached a certain age questions over style and direction arose between us, and John encouraged caution over the experimental ethos that surrounded the 1970s. I, on the other hand, just wanted to do whatever I liked! I don’t mind the musical comparisons made between myself and my father, as I can see this is naturally of interest to a general listener.

I find it difficult to make an objective assessment of my father’s worth as a composer, in the context of Aotearoa and our tradition. I remember composer and author Noel Sanders telling me that Lilburn regarded John Ritchie highly, as one of the country’s best composers. I take heart from this generous intimation from Noel. Purely at a technical level, I think John’s music, at its best, is top-quality and could grace any concert hall in the world. Writing in The Listener, Bruce Mason (the playwright) also expressed a similar view of Dad’s Concertino – it was world-class. Along with the Concertino, I would include his String Quartet, Brass Quintet, Suite for Strings No.1, The violin concerto Pisces and Papanui Road Overture in this category. He had a natural gift for melodic invention and development, along with a lively sense of rhythm, as well as a fine grasp of orchestration which influenced my own work. Although he didn’t write a lot of piano music, his Piano Concertino awaits to be re-discovered and his Three Caricatures are wonderful miniatures, in my opinion. Spurred on by this anniversary of John’s birth, I decided to ask a few composers who knew John to write something for piano. This was initially prompted by the sudden arrival of Three Preludinos based on a theme of John’s, by William Green, an Auckland-based pianist and composer. This was a generous gesture that my father would have appreciated hugely! Therefore, in the fullness of time, I will publish a short collection of piano pieces to commemorate the 100th anniversary of John Ritchie’s birth in 1921, and a concert/recording will be arranged. RNZ Concert is also planning a programme focused on John’s work in September.

By Anthony Ritchie, composer