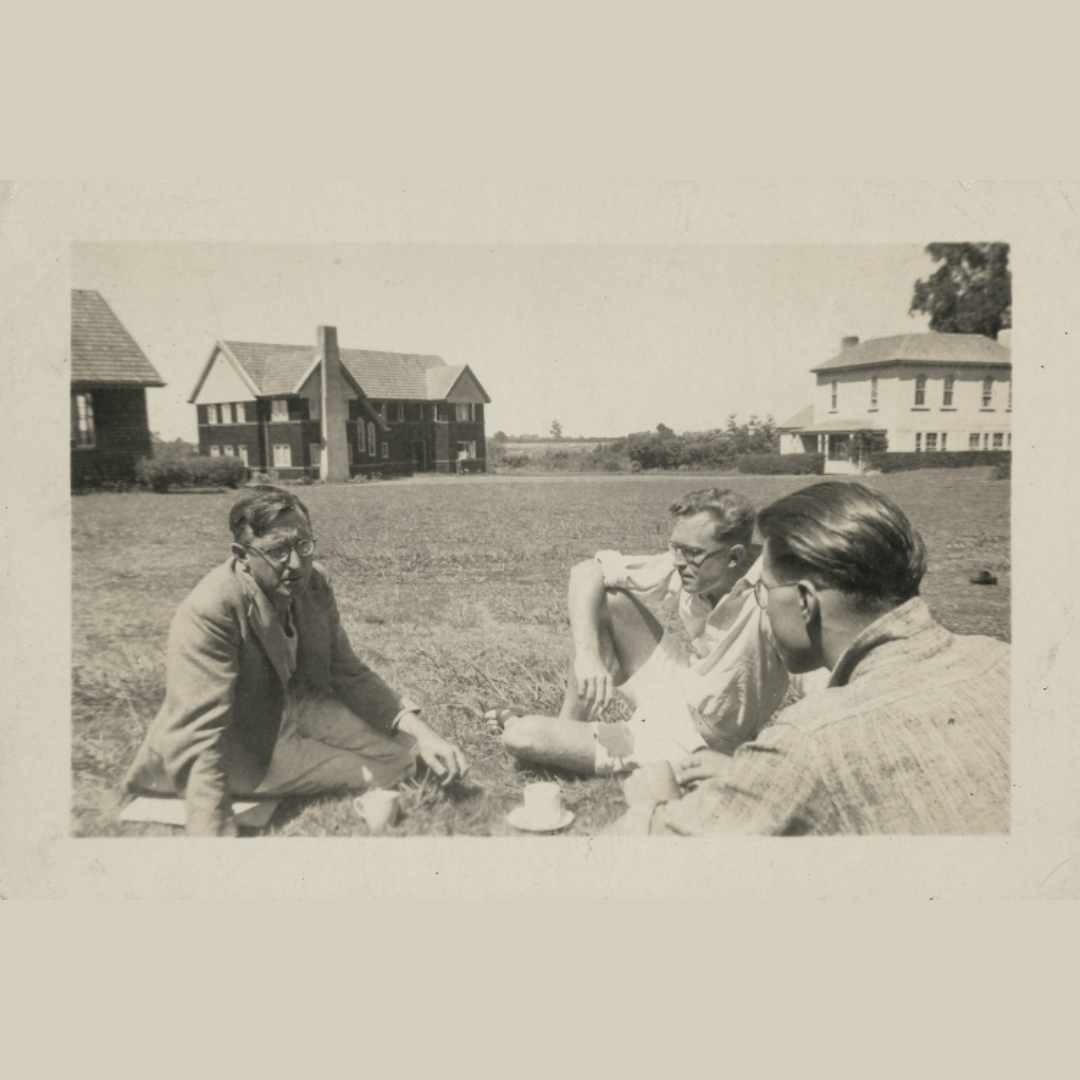

From left: Frederick Page, Douglas Lilburn and David Farquhar in 1948 at the Cambridge Summer School, Cambridge, New Zealand.

Ref: PAColl-7681-3. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22740090

An astute critic, Frederick Page was singularly opinionated. Armed with an inquisitive ear from day dot, he was encouraged to develop his own critical response to new work while he was studying in London under Ralph Vaughan Williams. “In New Zealand, I had read and read about music and had accepted second-hand opinions of others. My bluff was called when I had to make up my own mind about a new work.”

And he was spoilt for choice. In the years between 1935 and 1938, Page heard new Schoenberg, Walton and Bax, airings of Mozart’s operas, and both thrilling and resentful performances of Bartok, Berg, and Stravinsky. He was cautioned away from Webern and Berg and Stravinsky, to be later called upon to wonder at the bass part in Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms. As it turned out, the people around Page were more focussed on the work of Hindemith, Sibelius, and the new English school. As the musical tide ebbed and flowed, he found himself blessed with the enviable position of having much more music available to him than he could possibly chew on.

In the late 1930’s after a bout of illness, Page returned to New Zealand. He was later followed by artist Evelyn Polson, the two marrying in Christchurch. Initially turning down a position as a critic at the Listener (though he did later write for them), Page put his critical finesse to work at the Christchurch Press. Alas, it was short-lived. Fred was asked to resign after the editor had been pestered by the fathers of Page’s subjects—supposedly he had not dutifully recognised their genius. His response: “No, I’d prefer to be sacked.” And so, he found himself unemployed for but a day, before hearing word that he had been appointed to the new Department of Music at Victoria University College—what is now New Zealand School of Music—Te Kōkī.

Along with Lilburn, who was hired following a need for a dedicated composer on staff, Page quickly gained a reputation among the local music teachers for eschewing classical harmony training—what he called “nun’s counterpoint”. Instead he taught ear-training, and after a trip back to Cambridge and Oxford, began distributing the works of the time: pieces by Boulez, Stockhausen, Berio, Messiaen, Copland, and works by New Zealanders Tremain, Pruden, McLeod, Lilburn, and Farquhar. Once he had built up enough leave, and at the suggestion of Schoenberg’s nephew, Richard Hoffman, Page made the voyage to the Darmstadt Summer Course.

Darmstadt 1958—the year Page was in attendance—was the year John Cage scandalously claimed that there was as much beauty in the sound of a cowbell as in anything he could find in Beethoven. Page attended performances of Boulez’s Le Soleil des Eaux, and Nono’s Doro di Didone, and found himself refreshed by tactful playings of Schoenberg in the hands of expert performers.

After the musical shake-up that was the Darmstadt Summer Course, he was drawn to Venice by the mention of a debut performance of a new Stravinsky work—Threni. By chance or fateful design, Page walked past a theatre from which he heard the unmistakable sounds of the Rite being rehearsed. Upon further inspection (and after sneaking past the theatre attendants), Page found himself across the aisle from the maestro himself. As he writes, “[Stravinsky] clasped both my hands and warmly thanked me for sending him a programme of our Wellington concert. ‘But I wrote to thank you and my letter was returned: you have an inefficient postal service in New Zealand." Fred had previously made Igor a patron of the Victoria University College Music Society, and given a concert of his works. Eventually, Stravinsky would return the favour, visiting Wellington in 1961, attending rehearsals and performances of students at the time.

Moving on from Venice, Fred went to Donaueschingen for the Music Days, where he was dazzled by Stockhausen’s Gruppen for three orchestras, and puzzled by the battery of loudspeakers in Boulez’s Poésie pour pouvoir. Page ran into Boulez later, at a conference in Paris. Out to dinner with the composer, he pressed Boulez about future performances in Wellington and asked about the seemingly out-of-place instruments he called for. In the end, Page was given scores to bring back to New Zealand, to further bolster the library shelves.

Page’s unflinching dedication to new sounds left an indelible mark on New Zealand’s ‘classical music’ output. Passing in 1983, Fred was missed by Boulez when he visited New Zealand five years later. His legacy lives on in the musicians who similarly seek the new and exciting. And perhaps those scores of Boulez still live in the Victoria library?

Source: A Musician’s Journal, edited and arranged by J.M. Thomson and Janet Paul